Table of Contents

Why accurate HS classification is the linchpin of modern trade compliance

Misclassification is expensive. One retailer, Z Gallerie, agreed to pay 15 million dollars to resolve allegations it misclassified wooden bedroom furniture to avoid antidumping duties [reference:2]. That was not a rounding error. It was a hard lesson in how a wrong code can morph into an enforcement case, reputational damage, and a massive check.

Customs tariff classification sets your landed cost. It determines base duties, triggers additional measures like antidumping or countervailing duties, and gates eligibility for preferences. Get it right and your landed cost is predictable. Get it wrong and you either overpay quietly for months or underpay and invite penalties when someone looks closer.

It also dictates risk and speed. Officers and auditors start with your HS code. It drives which admissibility rules apply, which partner agency flags fire, and whether your shipment sails through or gets parked for an exam. A defensible HS code is your first line of risk control and your fastest path to release.

Here is a nuance that seasoned pros know: classification errors are common, but only a subset actually change the duty owed. CBP’s compliance measurement work has long observed high performance in revenue collection even when classification errors show up in audits, because many of those are non‑revenue mistakes that shift goods between same‑rate or duty‑free provisions [reference:1]. That does not make them harmless. Non‑revenue errors still burn time, invite queries, and erode credibility. Revenue‑impacting errors can add up quickly and can turn into enforcement if they look intentional.

The hardest part today is the data fog. You’re mapping from messy, natural‑language product descriptions to legal texts. At the same time, tariffs don’t stand still. Rates move. Quotas fill. Safeguards and special measures appear. Static spreadsheets cannot keep up, which is why live context has become the quiet advantage of top compliance teams. We will lean on it in this guide, but we’ll start with the legal backbone so your decisions stand on their own.

Here is what you will get by reading this guide end to end:

- A step‑by‑step method to go from natural‑language descriptions to a defensible HS code

- How to surface live tariff context while you classify, so you see cost and risk in real time

- A validation checklist that aligns to the GRIs, legal notes, and WCO guidance

- A practical way to compare candidate codes side by side and choose confidently

- An export workflow to push mappings to ERP, your broker, and reporting without per‑match fees

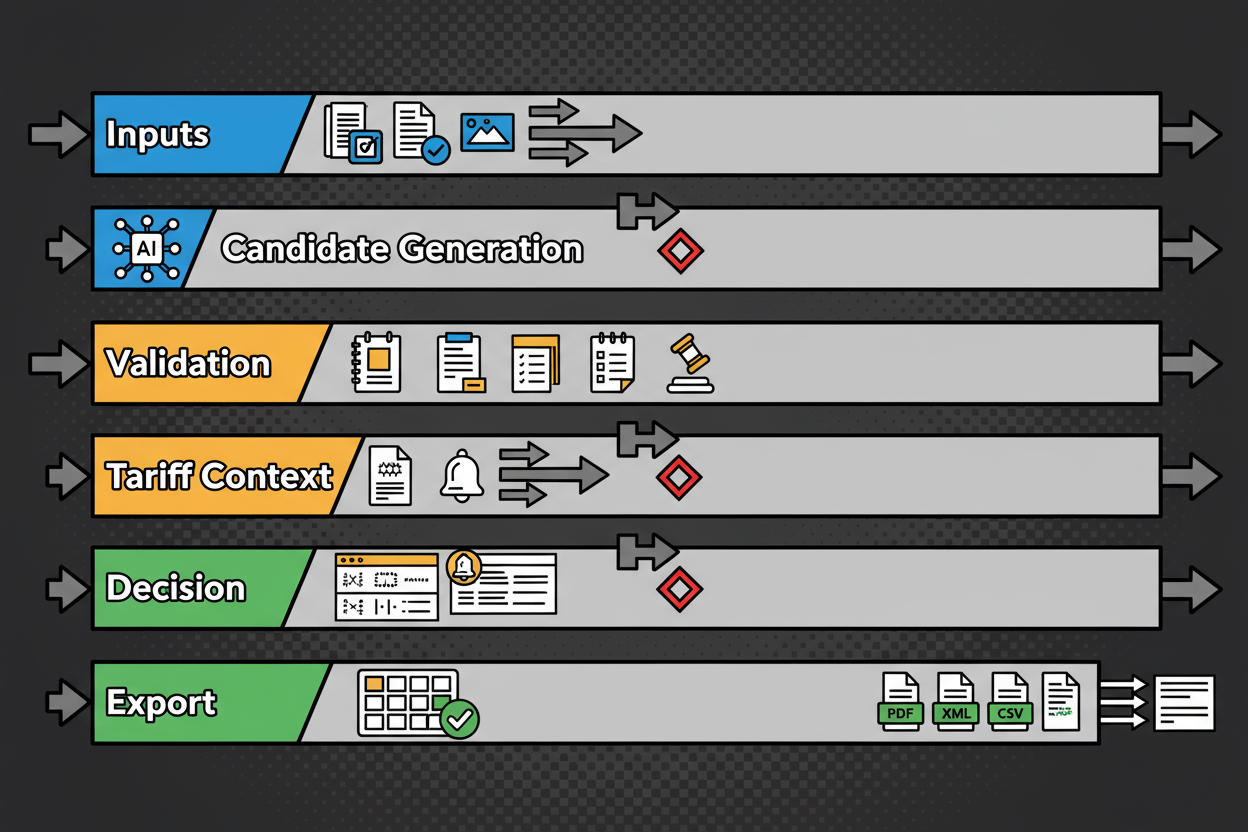

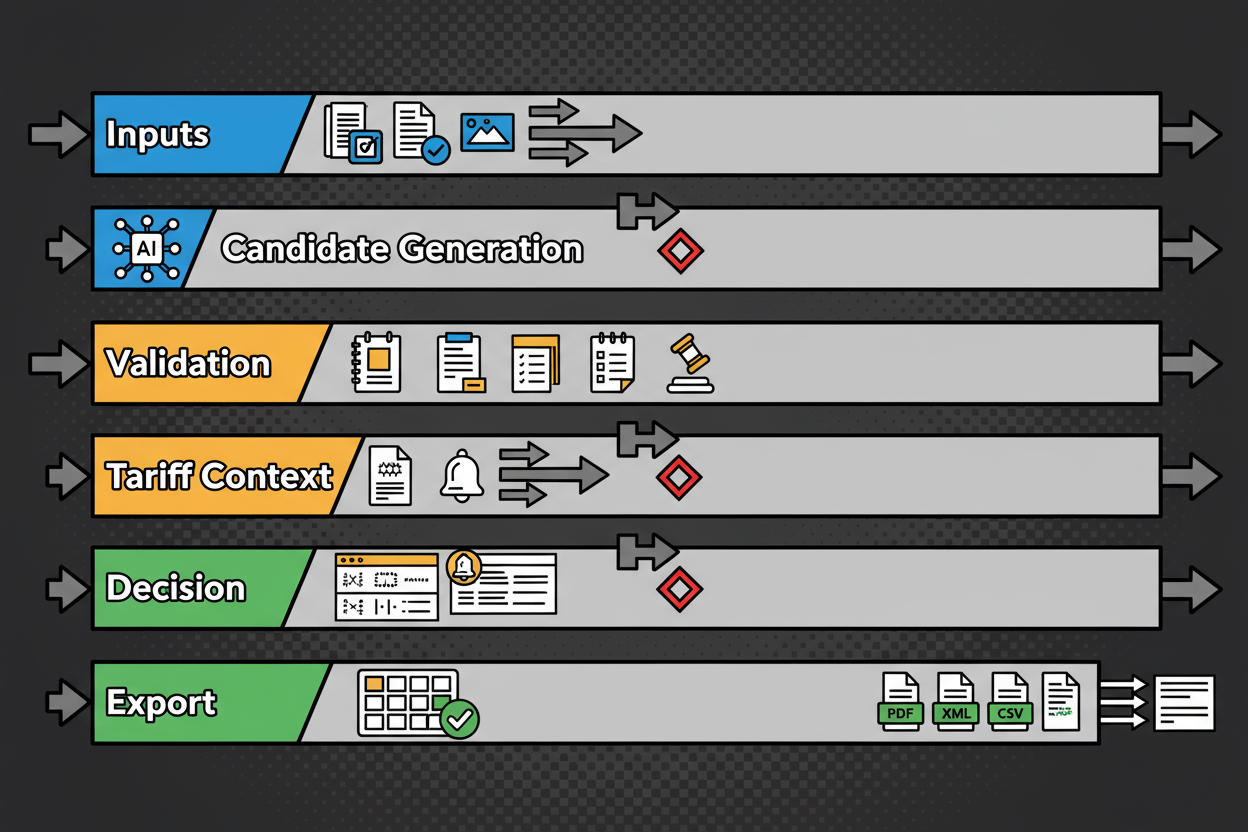

To orient you, this is the workflow we will follow from input to export.

We will keep it practical, cite the World Customs Organization where it matters, and show you how to document each choice. By the end, you will have a repeatable path for customs tariff classification that your auditors, brokers, and CFO can all get behind.

Understanding the Harmonized System: structure, rules, and common pitfalls

Let’s ground the basics fast, the way practitioners use them in real work. The Harmonized System (HS) is the global naming and numbering framework administered by the World Customs Organization. At its core are the HS Nomenclature texts (Sections, Chapters, headings, and subheadings), the General Rules for Interpretation, and the legally binding Section and Chapter Notes [reference:3]. The first six digits of a code are harmonized worldwide. Many jurisdictions then add national digits beyond six to handle tariff lines or statistical splits [reference:3].

Think of it as a tree. Chapters set broad families. Headings narrow scope. Subheadings refine within the heading. National extensions handle local tariff detail. The law tells you to read the actual words of the headings and the relevant legal notes first, not the titles or your intuition [reference:3].

Now, the General Rules for Interpretation (GRIs) are the roadmap. They are part of the HS legal instrument, and the official wording is published by the WCO in the HS Nomenclature and on the WCO Trade Tools site [reference:3]. We will paraphrase the ones you use most, then apply them in the next section.

Start with Rule 1. It tells you to classify according to the terms of the headings and the relevant Section or Chapter Notes. The titles are just guides. This is where most correct classifications are settled if you read the legal notes carefully [reference:3].

Rule 2(a) expands a heading that names a finished article to also cover an incomplete article that has the essential character of the finished one, or the same article presented unassembled. Think flat‑packed furniture or a bicycle missing a wheel. If it looks and functions like the finished thing in substance, Rule 2(a) keeps you in the same heading [reference:3].

Rule 2(b) covers mixtures and goods of more than one material. It says that a heading that names a material also covers mixtures or combinations of that material with others, subject to the later Rules. When a product blends materials, you will often end up in Rule 3 to resolve which heading wins [reference:3].

Rule 3 is where you live for sets, composites, and multi‑purpose goods that appear to fit more than one heading. The sequence is simple in concept: choose the most specific description if one is genuinely more specific, or if that does not resolve it, pick the heading of the component that gives the goods their essential character. If even that fails, select the heading that appears last in numerical order among the candidates [reference:3]. Essential character here is a practical test. You look for the component or feature that drives performance or consumer choice.

Rule 5 gives special treatment to containers and packing. A fitted case that is clearly designed and shaped for a specific article, and that is presented with it, typically travels with the article when you classify the set [reference:3]. Everyday shipping cartons usually follow the goods too, but with exceptions you should check.

Rule 6 repeats Rule 1 at the subheading level. Once you are in the correct heading, you apply the texts of subheadings and any Subheading Notes within that heading, in the same disciplined way, to reach the final six‑digit result. National splits come after [reference:3].

What about the Explanatory Notes and Classification Opinions? The WCO publishes Explanatory Notes to clarify the scope of headings and subheadings and to provide examples and interpretation. They are not binding law under the HS Convention, but they are the official commentary and are highly persuasive worldwide. Many jurisdictions instruct decision makers to have regard to them. WCO Classification Opinions are case‑specific examples that guide consistency across countries [reference:3].

National rulings sit below that in the hierarchy. In the United States, CBP binding rulings apply to CBP and the party to whom the ruling was issued for the specific described goods and facts. They are not legally binding on other importers, though they are often cited as persuasive precedent. If you want protection, you get your own ruling. Prior rulings in the CROSS database help you build your case but do not bind CBP in your situation if the facts differ or the law has changed [reference:4].

Now for the traps that trip up even experienced teams. Each one ties back to a Rule or a legal note.

- Function vs material: Don’t default to the material if a functional heading more specifically covers the product. Test Rule 1 first with the legal notes, then Rule 3(a) on specificity [reference:3].

- Kits vs sets: Only certain retail sets get Rule 3(b) essential character treatment. Loose assortments are classified piece by piece. The Explanatory Notes to Rule 3 guide this distinction [reference:3].

- Composite goods: Blends of materials or combined machines often require Rule 3(b). Evidence for essential character matters, not just gut feel [reference:3].

- Parts vs accessories: Section and Chapter Notes often define parts. Some notes exclude parts of general use from “parts” headings. Read the Notes before assuming a parts heading applies [reference:3].

- Principal use: For headings controlled by use, analyze the principal use in your market, not occasional uses. The Notes and EN examples shape this analysis [reference:3].

If you remember one thing about HS structure, make it this: legal notes control. Always cite the exact Note that includes (or excludes) your product. Then, if you need interpretation, lean on the WCO Explanatory Notes. If you rely on a national ruling, state clearly whether it binds you or merely supports your reasoning [reference:3][reference:4].

With that legal scaffolding in place, let’s walk a real product from messy description to a defensible code.

From description to code: step‑by‑step classification using natural language

We will classify a cordless drill kit that includes the drill, a lithium‑ion battery, a charger, and a fitted carrying case. This is a classic multi‑component scenario that forces you to apply Rule 3(b) and consider Rule 5(a) for the case.

First, extract the attributes that actually drive HS classification. Most product blurbs are noisy. You want the features that map to headings and legal notes.

- Function: hand‑held power drill for drilling holes and driving fasteners

- Power: self‑contained electric motor, battery operated

- Components included: one drill body, one Li‑ion battery pack, one charging unit

- Packaging: molded, fitted hard case designed for the drill and accessories

Next, identify the prima facie candidate headings under Rule 1 by reading heading texts and the relevant Section and Chapter Notes. The drill appears under the tools heading for hand‑held tools with a self‑contained electric motor. The separate battery could fall under the batteries chapter, the charger under electrical transformers or power supplies, and the case under trunks and similar containers. You now have multiple headings that seem to apply to parts of the bundle [reference:3].

That brings you to Rule 3. Because the goods are put up together for retail sale and are prima facie classifiable under more than one heading, you apply the sequence in Rule 3. The most specific description test in 3(a) does not resolve it because different headings specifically describe different components. So you move to 3(b), the essential character test for sets and composite goods [reference:3].

Which component gives the kit its essential character? The drill. It performs the core function the consumer is buying. The battery and charger are enabling components. The fitted case protects and presents the main article. The Explanatory Notes to Rule 3(b) discuss similar examples where the functional article imparts the essential character in a retail set [reference:3]. On that basis, you classify the kit as a drill under the hand‑held electric tools heading.

Before you lock that in, consider Rule 5(a). The case is specially shaped and fitted to contain the drill and accessories and is suitable for long‑term use. When presented with the drill, such cases are classified with the article. That supports keeping the case within the drill classification, rather than classifying it separately under containers [reference:3].

Now apply Rule 6 to pick the subheading. Within the hand‑held electric tools heading, look for the subheading that covers drills with a self‑contained electric motor. Read any Subheading Notes. Then choose the correct six‑digit subheading by the terms of those subheadings, mirroring the disciplined approach of Rule 1 at this level [reference:3]. If your market requires national extensions beyond six digits, you would continue through the national tariff splits using the same logic.

Two final validation touches make this airtight. First, open the Explanatory Notes for the relevant heading and for Rule 3(b). If there are examples of drill kits or analogous sets, capture those excerpts in your evidence file to show the interpretation path you followed [reference:3]. Second, search national rulings databases for similar sets. In the United States, a CBP ruling on a comparable drill kit can be persuasive support, but it does not bind CBP for your imports unless the ruling was issued to you for the same goods and facts. Treat third‑party rulings as helpful precedent, not as law you can rely on without question [reference:4].

You now have a defensible HS code derived from the legal texts and the GRIs, with a clear reasoning trail. In the next part of the guide, we will layer in live tariff context so you can see duty rates, additional measures, and quota signals at the exact moment you make the call.

Surfacing live tariff context: duty rates, quotas, safeguards, and amendments

You now have a defensible HS code. Great. Next, you need to see what that code actually costs you today and what risks ride along with it.

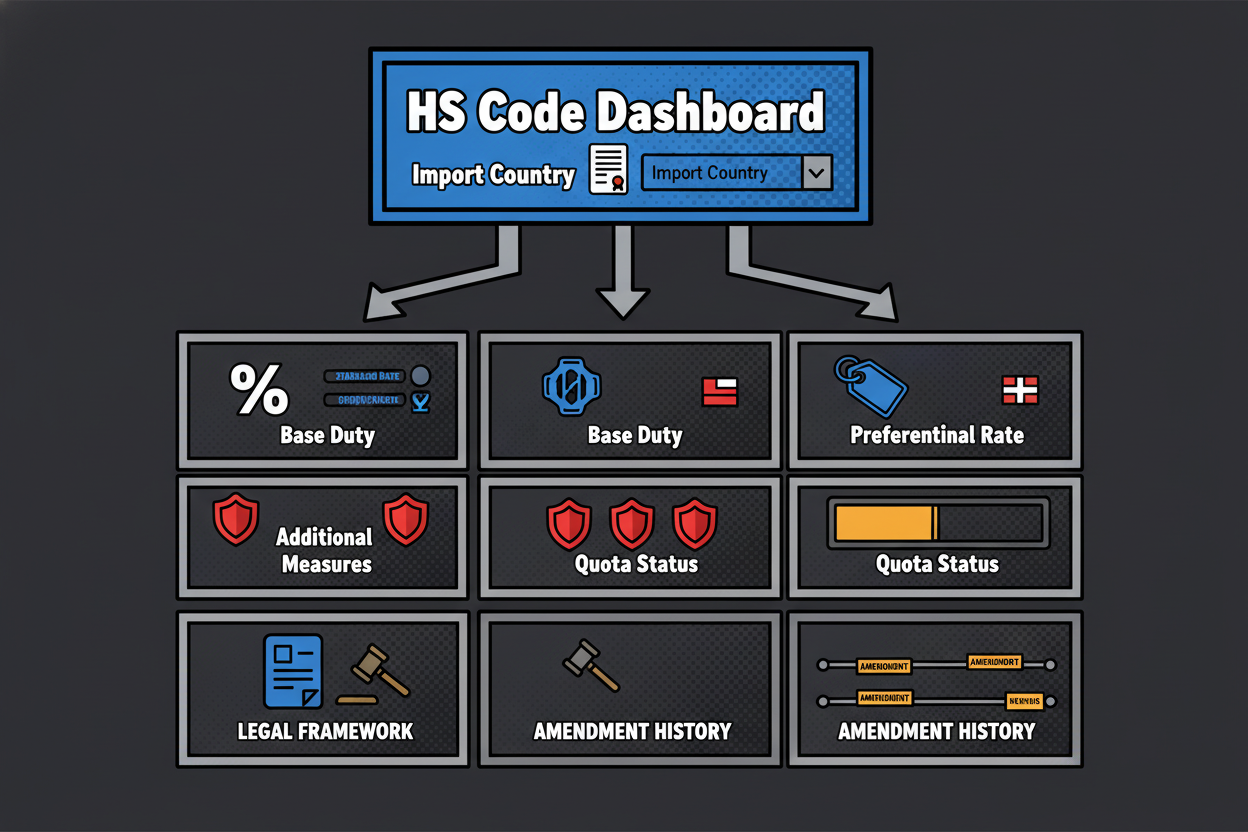

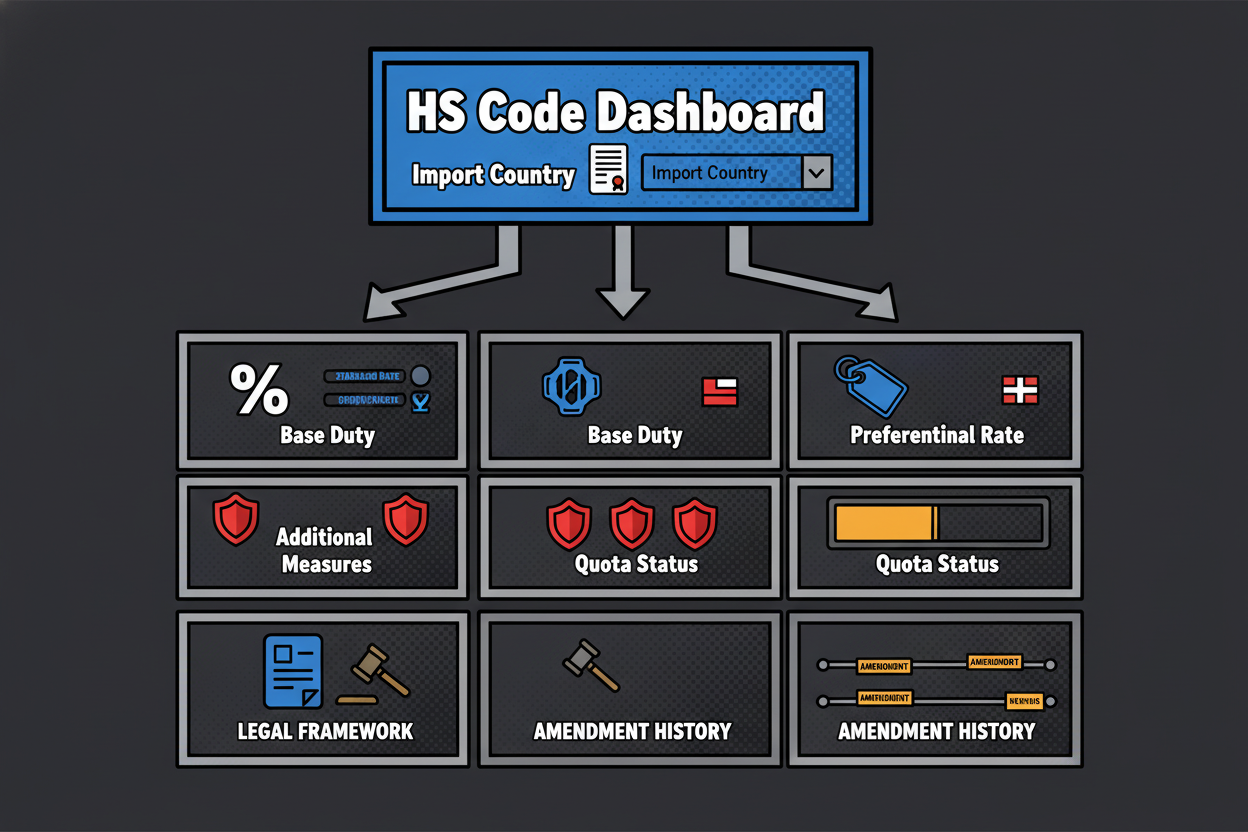

Live tariff context is the real-time picture around a tariff line. It shows the base duty, any preferential duty by origin, plus everything layered on top, like additional duties, quotas or tariff rate quotas, and safeguards. Think of it as the operational lens you apply to the legal classification you just finished. You still start from the HS structure and GRIs, then read measures and rates that your market applies to that code [reference:3].

Here’s what “live” typically includes for customs professionals:

- Base or MFN duty rate for the importing country, preferential rates by origin, and seasonal rates if the line changes in defined windows

- Additional measures: surtaxes, anti-dumping, countervailing, and safeguards that sit on top of base or preference

- Quotas and TRQs with current fill status, remaining quantity, and thresholds

- Amendments and scope updates on the code or measures, plus notes or rulings that affect interpretation [reference:3]

Why does this matter? Because the HS gets you to the correct legal box, but duties and measures change. Some measures turn on or off with quota fill. Some apply only with certain origins. Static PDFs can’t capture that movement. The WCO provides the legal scaffolding for classification and publishes the official HS and Rules, while national tariffs layer on current measures and rates. Treat the HS texts as your legal base and use live national tariff data to capture current application [reference:3].

Let’s unpack the moving parts you’ll read in a live panel.

Base and preferential rates. The base, often called MFN, is your default. Preferential shows what applies if your origin meets a trade agreement’s rules. Some lines are seasonal. If the code has seasonal periods, the panel should show which period you are in and the rate in effect.

Additional duties. These are the silent budget breakers. Anti-dumping and countervailing duties target unfair pricing or subsidies. Safeguards respond to import surges. Surtaxes and special measures can appear on short notice. Your live panel should flag them clearly so you don’t rely on a base rate that looks harmless while a large additional duty actually applies [reference:3].

Quotas and TRQs. A quota is a hard cap. A TRQ splits a quantity into two bands: a lower in-quota rate up to a limit and a higher over-quota rate after. You want three things here: the unit of measure, the total in-quota quantity, and the current fill status. A progress bar or a remaining-quantity figure lets you plan timing. If you rely on a lower in-quota rate for pricing, you need alerts as the fill rate approaches the ceiling.

Amendments and updates. Tariff lines can change text, notes, and rates. New classification opinions or national rulings can shift practice. While the WCO manages HS updates and explanatory guidance, national administrations update rates and measures whenever policy requires. You want an update feed that tells you when a rate changed, a note was adjusted, or an administrative ruling impacted scope, so you can re-validate key SKUs at the right time [reference:3].

How often does this move? In practice, base nomenclature has structured cycles, and national measures update as policy changes. That’s why static spreadsheets or PDFs are risky. You lose the thread on mid-cycle actions like a TRQ opening, a safeguard trigger, or a measure suspension. Live context keeps your costing and compliance aligned to what’s in force now [reference:3].

Before and after: the cost of classifying without live context

Picture a small appliances importer classifying a multifunction kitchen machine. Their static sheet shows a base rate that’s attractive. They pick a subheading, lock pricing, and ship. Only later do they learn that for their origin, an additional duty applied to that heading, while a near-by subheading carried no additional measure but a slightly higher base rate. Net effect: the static pick looked cheaper but cost more because of the added measure.

Now replay with live context on screen. The candidate comparison shows the base and preferential rates for both options, plus a red badge on the additional duty for the first choice. The second choice has no additional measure, and there’s no TRQ. The team chooses the second subheading, avoids the added duty, and documents the decision logic. That is the difference between hoping your static data is current and proving your decision with what is actually in force.

Validation, comparison, and export: streamlining your classification workflow

You’ve got a candidate code and live context at hand. Lock it down with a validation flow that stands up in an audit. Keep it simple, consistent, and evidence-first.

- Record the GRI path: which Rules you applied and in what sequence, from Rule 1 through Rule 6 as needed [reference:3]

- Cite the exact legal texts: heading terms plus any relevant Section or Chapter Notes that control scope [reference:3]

- Add Explanatory Notes excerpts and any WCO Classification Opinions consulted, as persuasive support [reference:3]

- Check national rulings: if your jurisdiction has a rulings database, capture relevant IDs and note they are persuasive unless issued to you; in the U.S., CBP binding rulings bind CBP and the requester but not third parties [reference:4]

- Attach your live tariff snapshot: MFN and preferential rates, measures, TRQ status, and any alerts you relied on

- Timestamp everything and sign off internally so you can show who decided what and why

With your evidence in place, compare candidates side by side. Bring legal fit and cost into the same frame so stakeholders see the full picture.

Candidate HS code comparison

| Field |

What to capture |

Why it matters |

| Candidate HS code |

Heading/subheading under consideration |

Anchors legal scope to specific text |

| Legal scope summary |

Plain-language summary of heading/subheading text |

Ensures you classify by terms of the heading (GRI 1) [reference:3] |

| Relevant Section/Chapter Notes |

Specific notes that include or exclude product features |

Legal notes control scope; cite note identifiers [reference:3] |

| Explanatory Notes excerpts |

Key EN guidance supporting inclusion/exclusion |

Persuasive interpretation and examples [reference:3] |

| GRI path applied |

Rules invoked (e.g., 1, 3(b) essential character, 6) |

Documents interpretative logic [reference:3] |

| Product-feature fit |

Yes / Partial / No, with 1-line justification |

Makes fit transparent to reviewers |

| Rulings alignment |

Related rulings IDs and stance, noting binding vs persuasive |

Adds persuasive support; third-party rulings are not binding [reference:4] |

| Duty impact |

Base/MFN rate and preferential rate (if origin known) |

Cost impact comparison across candidates |

| Additional measures |

AD/CVD, safeguards, excise, surtaxes, with flags |

Highlights risk or cost beyond ad valorem rates |

| TRQ exposure |

TRQ presence and current fill status |

Availability and timing implications |

| Risk notes |

Scope ambiguity, exclusion notes, interpretative risks |

Supports internal risk decisioning |

| Evidence references |

Links or IDs to notes, ENs, rulings, internal memos |

Traceability for audits [reference:3][reference:4] |

| Comparative score |

1-5 score on fit and risk with brief rationale |

Roll-up to select final code |

Example comparison for the cordless drill kit:

| Field |

Example entry – A |

Example entry – B |

| Candidate HS code |

8467.21 |

8507.60 |

| Legal scope summary |

Hand-held tools with self-contained electric motor, drills |

Lithium-ion batteries |

| Relevant Section/Chapter Notes |

Section XVI notes on parts and composite goods; Chapter 84 notes on tools |

Section XVI notes excluding parts of general use from parts headings |

| Explanatory Notes excerpts |

EN to 84.67 covers hand-held drills; EN to Rule 3(b) on sets |

EN to 85.07 covers accumulators, not sets dominated by a tool |

| GRI path applied |

Rule 1 for heading; Rule 3(b) essential character of retail set; Rule 5(a) case with the article; Rule 6 for subheading [reference:3] |

Rule 1 would only apply if classifying the battery alone; fails Rule 3(b) for the set [reference:3] |

| Product-feature fit |

Yes – drill imparts function; battery and charger support |

No – does not reflect the main function of the retail set |

| Rulings alignment |

Similar CBP rulings on drill kits support Rule 3(b) outcome (persuasive) [reference:4] |

Not aligned for retail kit context |

| Duty impact |

See live panel for MFN/preferential by market |

See live panel; would misstate cost for the set |

| Additional measures |

None flagged for the tool line in example market |

N/A for the set |

| TRQ exposure |

Not applicable |

Not applicable |

| Risk notes |

Ensure no more specific subheading applies within 84.67 |

Misclassification risk and audit exposure |

| Evidence references |

GRI pathway notes, EN 84.67, EN Rule 3(b), internal memo |

N/A |

| Comparative score |

4.8/5 |

1/5 |

You can run the same grid for any product family. The structure forces clarity. Legal fit comes first. Cost and measures ride second, but they sit in the same view so decision makers see the trade-offs.

Export your mappings without per-match fees

Once a code is validated, you need it where work happens: ERP, broker portals, purchase systems, and BI dashboards. That means structured exports with evidence fields so your decisions remain traceable and easy to refresh.

Push codes out in the formats your stack expects. Include the SKU, the normalized description used for classification, HS code by market, duty rate and measures snapshot, evidence references, and a timestamp. Each export should log who exported what, when, and where it went. That single habit cuts audit scramble time dramatically.

Per-match fee models punish you for doing the right thing, like revalidating at tariff change or refreshing a whole catalog. A flat, unlimited export model encourages routine checks and batch updates. The difference shows up in both cost and risk behavior [reference:1].

Cost comparison: per-match vs unlimited export

| Dimension |

Per-match model |

Unlimited export model |

| Pricing unit |

Price per classified SKU or transaction |

Flat license for unlimited classifications/exports |

| Predictability |

Costs scale linearly with volume; budget volatility at peak cycles |

Stable cost; plan annually regardless of spikes |

| Update cadence cost |

Reclassification triggers new charges |

No incremental cost to re-export updated mappings |

| Team collaboration |

Disincentivizes re-checks due to cost |

Encourages peer review and periodic re-validation |

| ERP/Broker sync |

Costly to refresh entire catalog |

Routine batch exports without penalties |

| Total cost formula |

Unit price x monthly matches |

Flat fee + optional seats |

| Example scenario |

If unit price is X and 10,000 SKUs refreshed quarterly, cost = 40,000X per year |

Single license covers initial and quarterly refreshes at no extra per-SKU cost |

| Risk of under-classification |

Higher, due to cost avoidance behavior |

Lower, because reviews are not penalized |

When you stop counting clicks, your team focuses on quality: better evidence files, more frequent rechecks, and faster pushes to ERP and your broker. That is how you keep classification errors from becoming revenue-impacting surprises [reference:1].

Frequently asked questions: HS classification and live tariff context

Q: How often do tariff rates and measures change, and how should I track them?

A: The HS legal framework is stable and managed by the WCO, but national duty rates and trade measures change whenever policy requires. Use live tariff context so you see current MFN, preferences, measures, and TRQ status when you classify. Set alerts for amendments and scope notes so you can re-validate high-volume SKUs at the right time [reference:3].

Q: What if my product doesn’t fit any obvious HS code?

A: Work the GRIs in order. Test heading terms and legal notes under Rule 1. If more than one heading fits, apply Rule 3. If it still resists, Rule 4 points to the goods it most closely resembles. Document each step and cite any Explanatory Notes used to interpret scope [reference:3].

Q: How do I stay compliant when rulings or notes shift?

A: Keep an evidence file for each decision. If a WCO Explanatory Note or a national interpretation changes, you can revisit the exact logic you used and adjust. In the U.S., a CBP ruling protects the requester and CBP for the covered facts. Others may cite the ruling as persuasive, but it is not binding on them. Monitor for modifications or revocations and keep your internal mapping aligned [reference:3][reference:4].

Q: Can I automate classification for large catalogs without losing control?

A: Yes, but keep humans in the loop. Use AI to generate candidates and highlight relevant notes. Then a specialist applies the GRIs, checks Explanatory Notes, reviews any rulings, and records the GRI path. Export with evidence and timestamps so your automation stays auditable [reference:3][reference:4].

Q: How do I handle ambiguous or multi-use products?

A: For composites, mixtures, or retail sets, Rule 3(b) pushes you to essential character. If two headings remain equally plausible, Rule 3(c) picks the one that appears last among those considered. Always tie your conclusion to the wording of legal notes and capture EN excerpts that support your interpretation [reference:3].

Q: Where do Explanatory Notes and national rulings sit in my evidence file?

A: Start with binding texts: heading terms and Section or Chapter Notes. Add EN excerpts and any WCO opinions as persuasive guidance. National rulings sit below that. In the U.S., a ruling binds CBP and the requester; for everyone else, it is persuasive and should be cited as such with a note on its scope [reference:3][reference:4].

Modernizing customs classification for compliance and efficiency

When you combine a disciplined GRI-based process with live tariff context, you control both legality and cost. You reduce the risk of enforcement outcomes like penalty cases built around misclassification and avoided duties, and you catch non-revenue errors before they chew up your team’s time [reference:2][reference:1].

The workflow you saw is practical: extract attributes, generate candidates, validate with GRIs and notes, open live context, compare and decide, then export with evidence. That’s how high-performing teams cut through messy descriptions, moving tariffs, and audit pressure without slowing the business.

Here’s a tight checklist you can implement right away:

- Normalize product descriptions and extract classification attributes

- Generate candidate headings and read the legal notes under Rule 1 [reference:3]

- Apply GRIs 2 and 3 as needed, then Rule 6 at subheading level; capture EN support [reference:3]

- Open live tariff context to compare MFN, preferences, measures, and TRQs

- Document rulings alignment and whether any cited ruling binds you [reference:4]

- Decide, record the evidence and timestamp, and export to ERP and your broker

- Set alerts to re-validate high-volume SKUs when measures or notes change

Adopt this now, and your customs tariff classification stops being a fire drill and becomes a repeatable, auditable advantage.

Key Takeaways

- Classification decisions must start with the HS legal texts and GRIs; live tariff data shows cost and risk in force now [reference:3]

- Document your GRI path, cite legal notes and ENs, and note any rulings’ binding status [reference:3][reference:4]

- Compare candidates on legal fit and live measures in one view so cost and compliance move together

- Export mappings with evidence and timestamps, and avoid per-match fees that discourage revalidation

- Use alerts to recheck critical SKUs when amendments, measures, or TRQs shift, minimizing revenue-impacting errors [reference:1]